Learning to explore an art museum with my children is one of the most inspiring projects I’ve done. Last summer, we went to Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin to see a temporary exhibition questioning the boundaries of our political and social perspectives. You can read the specifics on the museum website. When I sit down to think about what I can learn from the experience, I realize my oldest hit the pin on the head in the first five minutes of our visit. If you’ve been following along as I learn to see art with kids, then you know we sat down on the floor, we laughed, and we probably danced. But let me tell you about the tantrum.

We’re finishing the first gallery (the main hall pictured above) and my oldest son (6) exclaims that he’s over it! We’ve only been there for a few minutes, and he’s done with all art. “It’s always confusing!” he explodes. And I reply with something like, “That’s life son.” During our short conversation where I try to diffuse my child and do justice to the value of art, I take the stance that art reflects life and life has more unclear moments than plainly understood parts. My motivational mom moment continues with how we practice skills like observing, sensing, and deciphering in a museum that we will need in everyday life to deal with confusion, sense good vs. evil, and identify our personal or cultural blindspots (two points for connecting the lecture to the curatorial intention). But he had a big point too… art is confusing. And there are a few artists who are doing it on purpose.

We’re finishing the first gallery (the main hall pictured above) and my oldest son (6) exclaims that he’s over it! We’ve only been there for a few minutes, and he’s done with all art. “It’s always confusing!” he explodes. And I reply with something like, “That’s life son.” During our short conversation where I try to diffuse my child and do justice to the value of art, I take the stance that art reflects life and life has more unclear moments than plainly understood parts. My motivational mom moment continues with how we practice skills like observing, sensing, and deciphering in a museum that we will need in everyday life to deal with confusion, sense good vs. evil, and identify our personal or cultural blindspots (two points for connecting the lecture to the curatorial intention). But he had a big point too… art is confusing. And there are a few artists who are doing it on purpose.

In the artwork, “The Jungle Book Project 2002,” Pierre Bismuth makes a Disney film confusing on purpose. Except the characters don’t seem confused. Just you. Bismuth edits the original sound, so that each character is speaking a different language. Mowgli is speaking spanish to Bagheera, who is speaking Arabic. The story moves along without missing a beat. There are 19 different languages. It’s melodic and raises questions the curators’ are asking about cultural boundaries and perspectives. But if you are a jet lagged kid who just wants to watch the Jungle Book movie while your parents look at art, you might get frustrated.

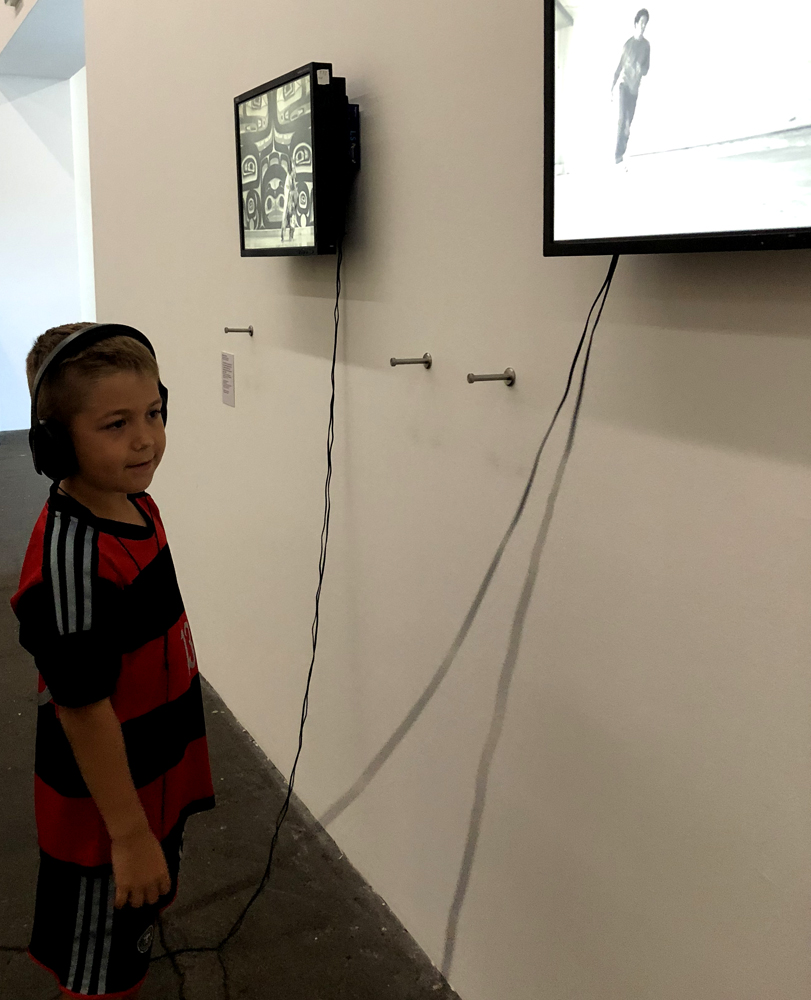

Like “The Jungle Book Project,” Nicholas Galnin’s black and white videos, “Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan,” mix up sound and image. About half way through the museum, we paused in front of two small screens with headphones dangling on the wall. A young, contemporary dancer grooves on one screen. A traditional Native American dancer performs the Raven Dance in another. We almost walked away before picking up the headphones and trading them back and forth. It takes a minute to decipher, but it seems Galnin has exchanged the music. The Raven Dance is performed to electronic music. The other dancer pops to the traditional Native American song Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan (which translates as “We will again open this container of wisdom that has been left”). Tethered to the wall by the headphone cords, we still decide to join this cultural continuum and joyfully dance. There is a lot of critique in the artwork, but it is also a hospitable invitation to widen my own perspective on the boundaries of my culture. And a family should dance together to music only they can hear in a place where no one else is dancing…right?

There were a lot of moments in the museum when one of us got excited about a piece and dragged everyone else to see it, but there is one last piece that gave me a fresh perspective on my relationship with my children.

And at the end of the Rieckhallen is a permanent installation by Bruce Nauman called “Room with my soul left out, room that does not care.” You have to decide how this one will make you feel, but the advantage of having children with me is that I can see how it made them feel. I didn’t tell my children the name of the artwork because I did not want it to set them up to fear. But I have one child who can smell despair in an artwork from a mile away and doesn’t want to be near it, he walked out. I held his hand as we walked back in together. The room is a conceptual space that is uncomfortable. However, the disturbance is only abstract, defined by minimal forms and light. One of my children was dancing in the shadows while the other bravely held my hand to navigate what he could not see but could sense. This artwork is a marker for remembering to walk with my children through the rooms of their soul…and even to care when the room doesn’t (wink).

Hamburger Bahnhof is the only remaining 19th century train station. The vastness of the main hall and the length of the former dispatch warehouses remind you that the building itself is a unique place to experience art. I was there last summer with my family, including my five and six year old sons. We saw the temporary exhibition “Hello World” together. It was huge: 400 artworks and 13 thematic chapters. That’s a lot of art for anyone to process at once, especially a child. We barely made it through the exhibition, and my children chilled out with a lollipop while I scooted around to anything I didn’t want to miss entirely. If you want to see everything in this art museum, then do not take little kids (ha). But learning to see (what we did see) in relationship with my kids was worth it to me. We finished the museum with a beverage in the courtyard before eating at a nearby Syrian restaurant and hunting for more Berlin playgrounds.