Open in New York City through March 12th at the EFA Project Space, The Let Down Reflex is a group exhibition including the work of Home Affairs, Dillon de Give, Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn, Leisure (Meredith Carruthers & Susannah Wesley), Lise Haller Baggesen, LoVid, and Shane Aslan Selzer. The curators brought these artists together to take a look at “the complexities of parenting in the art world.” The Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts Project Space lists upcoming events on February 27th, March 5th, and March 10th. Get over there if you can!

Home Affairs, an artist collective in The Let Down Reflex, is a collaboration between Arzu Ozkal, Claudia Costa Pederson, and Nanette Yannuzzi. They are skilled at creating dialogue. Their project, “And Everything Else,” not only raises the issues of parents but also questions our value of work vs. living. I’m excited for them to share more about why this conversation matters in the interview below.

Karen: Tell me a little about Home Affairs. How did you begin working together? How do you collaborate?

Nanette: Home Affairs grew out of a long term collaboration between myself and Arzu Ozkal and was prompted by the realization that we’d reached a point, both as individuals and collaborators, where we recognized that in order to grow the ideas we were most passionate about, we needed to include more voices. This prompted a discussion about who and how many to include. Claudia seemed a natural fit as she and Arzu collaborated before and I was a big admirer their Declaration of Sentiments- Gün collaboration. We were ecstatic that Claudia was interested in working together to shape the collective and things proceeded from there. The funny thing is, I’ve never met Claudia in person. We have a completely virtual collaborative relationship. It’s amazing that things have progressed so smoothly. We’ve all worked collaboratively in the past (and we each currently work on other collaborations outside of Home Affairs) and believe in it as a praxis.

Claudia: Home Affairs is just a handle for projects with feminist angles. I rather see it in part as a curatorial vector from which to introduce diverse voices by way of intersecting different venues and engaging with various people who are in various degrees concerned with progressive cultural change, and in particular with issues impacting women’s lives. Gün dealt with women’s access and role in shaping culture and cultural notions of gender in an increasingly conservative Turkey (Arzu is Turkish, and I worked with the Turkish diaspora in the Netherlands, where I lived before coming to the U.S.). Later in Greece we worked with women on the concept of home, as several curators there invited us to create a project reflecting on what it meant to be home in an increasingly connected world, and in the context of Greece facing a chilling economic downturn. Well, I am a daughter of political refugees from Portugal, so the home as such (as a global place, but also as a place left behind, and a place at the margins/at the mercy of the European political and economic center) is very familiar to me. And Everything Else, which consists of a series of images contributed by various women artists, mostly friends of Arzu’s and Nanette’s, just felt like a natural fit. The project is really another Gün, a space for women to connect, network, investigate, discuss, and share knowledge and information about issues that impact their lives.

Describe your project for Let Down Reflex.

Arzu: Our work addresses gender imbalances ingrained in the art world. We are particularly concerned with highlighting the invisible artist mother, the artist who is also a caregiver.

The gallery installation included 2 award letters presented to Women’s Studio Workshop and Ada Camp, which support creative practitioners who are also a caregivers. The gallery installation also included newsprint posters for visitors to take and distribute in their art communities.

Project Statement:

Art and caregiving intersect in the rhetoric of “labor of love”. In the art world, this belief is embodied in stereotyped notions of the artist. We are all familiar with them. There is the starving artist, the crazy artist, the hermit artist. And then there is the childless artist.

Automatically assumed to be a woman, the childless artist is center stage among the handful of women art stars. As the discourse goes, this is because art making is an all-consuming undertaking antithetical to childrearing.

By contrast, representations of ‘woman’ as caregiver abound in art. Images of the passive, self-less, self-sacrificing Madonna are emblematic. That both stereotypes overlay retrograde gender hierarchies and divisions of labor in art and care is corroborated by the numbers. According to a June 2015 article in ARTNews, the statistics relative to the number of women artists represented in major art museums and galleries remains dismal with the Hayward Gallery in the UK being the worst. Only 22 percent of their solo exhibitions were devoted to women in the past seven years. In the U.S., the Metropolitan Museum appears to suffer from a particularly harsh time warp. It appears that in 2012 only 4 percent of the artists they supported with exhibitions were women and that figure is worse than their 1989 figures. France isn’t far behind these bad boy scores. The Centre Pompidou has only dedicated 16 percent of its exhibition to women since 2007.

Parallel statistics report that women continue to bear the brunt of housework chores and child care. One recent government-funded survey suffices to put this in perspective: “men typically do about 9.6 hours of housework each week; women typically do about 18.1 hours. When it comes to child care, men average about 7 hours a week while women put in about 14 hours.” It appears then that the labor of love rhetoric permeating art making and caregiving is nothing but a metaphor for unpaid labor. And because of societal expectations, women artists are most impacted. Art institutions can and must play a role in changing these dynamics. The point is not to include women merely as tokens, but to structurally account for and support artists who are also caregivers.

How did your work resonate with the exhibition as a whole?

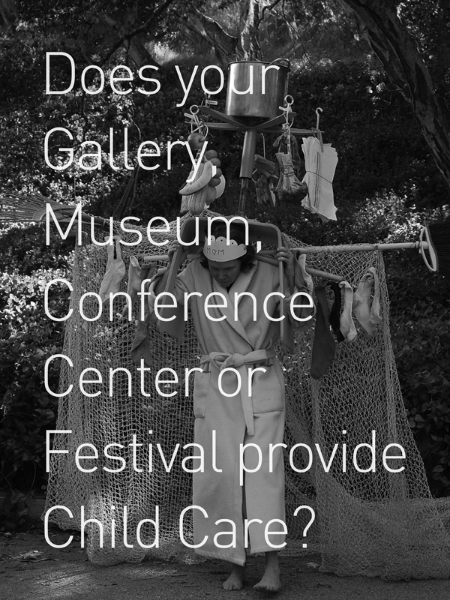

All of the work in the exhibition played off of one another in interesting ways. Ours played the role of ‘announcer’ in that our posters, images of artists/creative practitioners printed on newsprint with this on top: Does your Gallery, Museum, Conference Center or Festival Provide Childcare, were tacked grid-like filling a 10 x 11 foot wall. We also had piles of these take-away posters available to gallery goers as Arzu mentioned.

The curators talked about a “call to action.” What do you hope for as a parent who works in the art world?

Nanette: Even the words “a parent who works in the art world” read as something of a non sequitur…we read it, and it just doesn’t follow the apparent logic the words represent… Our hope is to contribute to changing this and to contribute to current dialogues around unpaid labor and parenting. Parenting, and other forms of caregiving can be a rich and vital part of an artist’s productive life and needs to be acknowledged via programming that supports working artists. Instead, what we have are ‘special circumstances’ of support and they’re few and far between. This is what our ‘Award Letters # 1 and # 2 are about. We’ve awarded particular institutions for developing programming that acknowledges that artists are often caregivers and as such, require particular kinds of support. We want these institutions to know we’re paying attention, and that we support and appreciate their efforts. We’re also beginning to form a registry listing who they are and what kinds of support they offer. So far the list is rather small.

Is “mom” really a bad word in the art world? I know when I was pregnant, I did not tell many work colleagues because of the culture of prejudice. But many of my friends in other sectors can’t believe it. How do you navigate it? What are the obstacles?

Arzu: Here is a story: When I began my tenure-track position in Fall 2011, I attended a new faculty orientation session, where faculty (all male) who already got promoted spoke to us about the tenure process. One of them pointed at the women in the room and said, do not get pregnant till you go up for tenure. (I already was!)

Nanette: Mom is not only a ‘bad’ word in the art world it’s a ‘bad’ word in academia. I hid my second BT (before tenure) pregnancy for four months. A month or so after I gave birth, one of my senior colleagues said to me, ‘he’s mighty cute but don’t get too distracted with this stuff, you’ve got work to do, you’ve got to keep up your production.’ The message was loud and clear, parenting and success are mutually exclusive. My response? I began bringing my son to department meetings and breastfeeding him. Why? At that time, 20 years ago, the only childcare provided in this small college town was far below standard. Basically, there was nothing within 20 miles. I was constantly stressed about finding childcare and yet realizing it was all substandard. They were the ones that needed to get the message, not me. Luckily, I was fortunate in that there were several forward thinking women in the department who were supportive.

The opening of Let Down Reflex encouraged children to attend. I take my children to art openings when it’s convenient, but they are often the only ones. Can you paint a picture of how it worked, pros, and cons?

Nanette: You know, it was interesting, the opening of The Let Down Reflex did have a lot of children in attendance and yet it seemed perfectly normal. Parents were there with their kids the same way they’re there with their kids at a parade, or a park. The curators made arrangements for strollers to be dropped off in a nearby room if need be, and day care was provided while we were installing the exhibition. I believe the pros and cons will work themselves out once we move past the idea that it’s a ‘special need’ and incorporate it into the whole of institutional operating budgets and structures.

I did have an interesting conversation with someone at the opening who talked about a large event he co-organized and the difficulties they’d encountered with, as he described, ‘getting parents who’d sign-up for child care to actually follow-through’ and vice-versa, ‘not being prepared for parents who showed up with children and expected that they be allowed to drop them off regardless of whether they’d signed-up’. Clearly there are state regulations mandating the number of childcare providers relative to the number of children in their care. At the same time, these are logistical challenges that are easily solved. The first thing we need to do is work toward an awareness. We need to change our consciousness to include the reality that artists/cultural producers are also parents, and that children are not appendages but in fact real people with needs. Once this shift in our thinking takes place then normative isn’t one thing it’s many, and can include the needs of a child, the needs of parents who are also artists, the need for wheelchair accessibility, or the needs of the deaf etc…

What do you hope the art world has for your children?

Arzu: A more welcoming environment. Children might not become artists when they grow up, but if they feel welcomed they will develop an understanding and appreciation. They will become the visitors and supporters of these spaces, and collectors of the work.

Claudia: There is actually a historical current of exhibitions and artists working with children in mind, in the United States tracing at least to Duchamp’s gallery intervention. Visitors to the opening of the First Papers of Surrealism exhibition in New York in 1942 were disorientated, not only by Duchamp’s famous ‘mile of string’ installation, but also by the presence of a group of children who, at Duchamp’s instigation, bounced balls and played hopscotch among them. Then in the sixties and seventies many artists in Europe, the United States, and Japan began engaging children in their works. Much of these legacies have to do with interests in play, one of my research concerns. The question of play in art has certainly many romantic connotations, but seen from the vantage point of politicized avant-gardes (Dada, Fluxus, Gutai, art and technology groups such as G.R.A.V., feminist artists, tactical media in the nineties, to name a few), the inclusion of children and play are profoundly political gestures. Children and play are not innocent, but ideologically charged notions, as is the “art world”.

I see our project as drawing from these legacies, and encasing them in the context of gendered labor. The gallery space as playground is really a very mild intervention into an environment that is historically rabidly exclusionary of women artists and their concerns. Therefore children in the gallery. It is the least that the art world can do in return in recognition for women’s double exploitation as artists and as mothers, both occupations underpaid or unpaid. The other alternative and what I hope to see happen someday is a fair wage for artists and caretakers.

What has been your favorite experience of art with a child/children?

Arzu: My son likes “exhibition cookies”. He is 4, he only cares about the catering.

Nanette: My children are 16 and 20 years old and have grown up going to art openings, mostly on college campuses but not exclusively. Their father and I were very assertive about their presence at these events and I believe that seeing the work of musicians, poets, theater people and visual artists, has shaped how they view the world. And like Arzu’s son, when they were little, they liked the catering most.

Favorite Children’s book:

Arzu: Onion’s great escape

Nanette: The Big Orange Splot

Claudia: Momo and the Time Thieves

Recent Art Read:

Arzu: Mothernism by Lise Haller Baggesen. She is one of the artists in the Let Down Reflex.

Nanette: The Artist’s Book as Idea and Form, Johanna Drucker, actually it’s a re-read.

Claudia: I am currently reading feminist science fiction, more fun than art ‘reads’.

All-time artist inspiration:

Arzu: Faith Wilding

Nanette: This question drives me crazy, there have been so many inspirations and many aren’t artists….but if I have to pick just one, it would have to be the one that was most formative for me as a young person, and that would be Frida Kahlo.